A colleague writes about Fidel: "He never accepted defeat;" and the thought goes to the reasons that made that characteristic of his, far from sterile obstinacy, a condition to turn utopia into palpable matter.It is not that he did not face adversities throughout his long life as a fighter and statesman; he had them and many -suffice it to mention the loss of his fellow Moncadistas, Alegría de Pío, the fall of very valuable guerrilla fighters, the disappearance of Camilo, the Bay of Pigs invasion, the October Crisis, the Flora cyclone, the murder of Che Guevara, the collapse of the socialist camp, the special period?-; but he knew how to see, after the painful balance of every setback, the genuine possibility of victory, and the imperiousness of never losing honor.It was not gratuitous optimism, but conviction of the rightness of the cause and its defense, and of the historical responsibility that the Cuban people carried on their shoulders, since they chose the star over the yoke.However, one step further, the Comandante was driven by the true belief in the Cuban people, in their intelligence and talent, in their capacity to perform the most unthinkable feats: "The efforts made by the people and the sacrifices made by the people have not been in vain, and if they did it once to conquer the revolutionary power, they will do it as many times as necessary to defend it."His vision of the country was not sustained on personalisms, but in his way of seeing and enhancing that "something" that the Island has -that is, its people- inexplicable to some, and that makes it rebellious, persistent, despite the difficulties: when it seems that there is no way out, Cuba reinvents itself."We bear our difficulties and our shortages with dignity, with the dignity of those who do not give up, with the dignity of those who will never get down on their knees," he said, and also that "among all and to all we have received much honor, much glory, much dignity, much shame! And we all have the right to the future, we all have the rays of dawn shining on us."If his words seem to have been pronounced for today, it is because he knew well the entrails of the enemy's ambition, and the sap of the Cuban nation: "The enemy's hope is that our great material difficulties will soften the people and bring them to their knees. Those are the dreams of imperialism, but they underestimate the powerful moral values, the powerful intellectual values and the powerful ideas that our people have today."We would have no problems, he pointed out, if the policy of the Government and of the Revolution had been the same policy of surrender that preceded it; the price of self-determination has been very high, like that of almost all worthwhile dreams. But he also warned about our shortcomings, because the strength of the Revolution, its advance, will depend on ourselves:"The greater or lesser difficulties that the Revolution will have will depend on no one but ourselves; because the difficulties that the enemy puts up are very logical, but the difficulties that many times with our incomprehension and with our foolishness we ourselves put up are very absurd, and against those we have to fight in every corner of the country."His call was to find solutions from each one of us, just as he believed that the people here could create, for example, their own computer, or their own vaccines.The thoughts of the Commander-in-Chief, a living source, and the teachings that emanate from him, should serve to unite us in the struggle of those who love and found. It is legitimate to think what would Fidel do today, but far from taking refuge in the "if he were here," we should ask ourselves what shall we do; this is the only way to ensure that he continues to be here, among the daughters and sons of a Homeland that has never accepted defeat.

Related News

Cuba appreciates donations from Slovakia and Japan

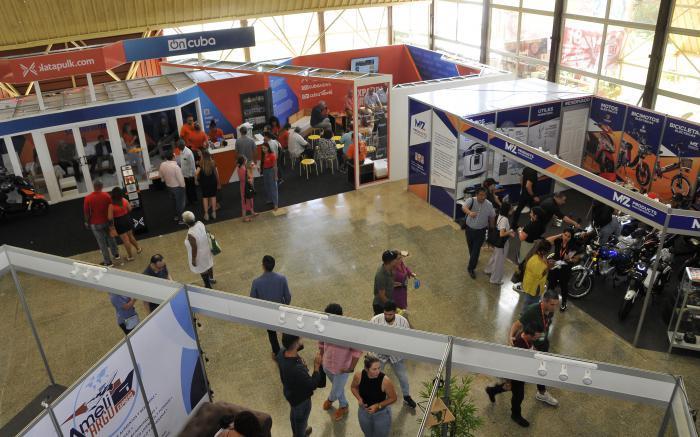

Cuba updates its portfolio of business opportunities

There are investments that are being worked on for the future of the country