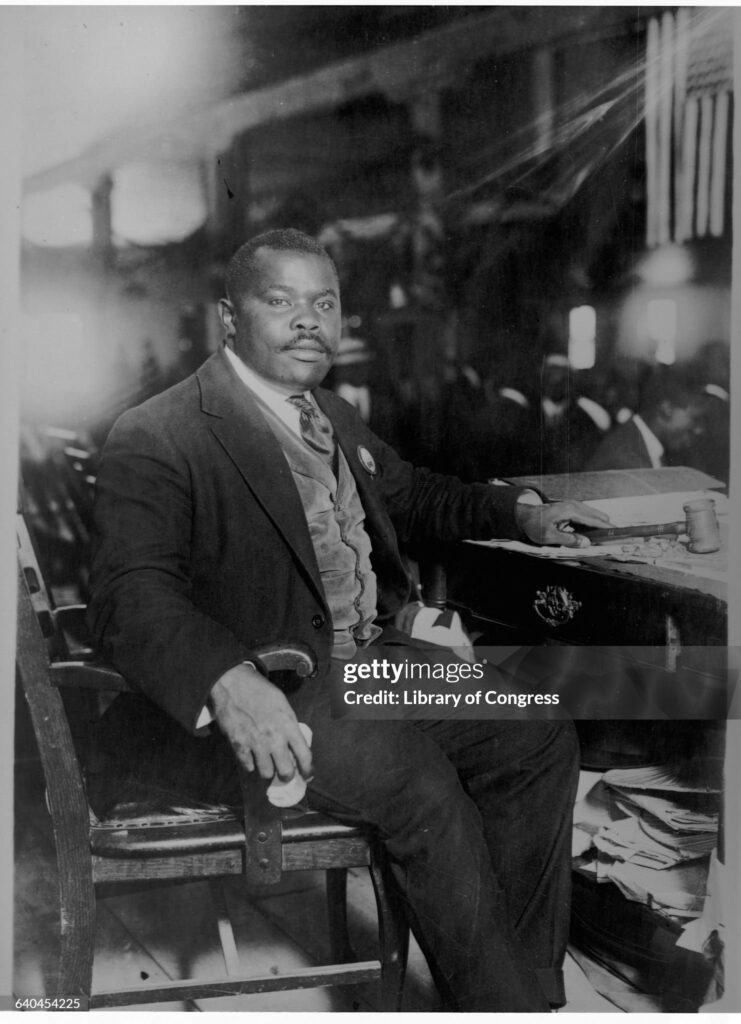

News Americas, NEW YORK, NY, Mon. Jan. 20, 2025: As Jamaica and the global Black diaspora celebrate the long-overdue pardon of the late Jamaican immigrant, civil rights, and human rights leader Marcus Mosiah Garvey by President Biden, here are ten key facts to know about this influential figure, who died 85 years ago.

1. Jamaican Roots and Early Life

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. was born on August 17, 1887, in St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica. As a teenager, he apprenticed in the print trade and later became involved in trade unionism in Kingston. His early travels took him to Costa Rica, Panama, and England before returning to Jamaica, where he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in 1914.

2. Founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA)

In 1916, Garvey migrated to the U.S. and established the UNIA, a movement that aimed to uplift Black people through economic empowerment and self-reliance. He declared himself the “Provisional President of Africa” and launched initiatives to unite the African diaspora globally.

3. Economic Empowerment Through Business Ventures

Garvey believed in Black economic independence and established various enterprises, including the Negro Factories Corporation and the Negro World newspaper. In 1919, he became president of the Black Star Line, a shipping company intended to facilitate African-American migration to Africa and promote trade among people of African descent.

4. Controversial Relationship with the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)

Garvey was one of the first Black leaders to meet with the Ku Klux Klan, a controversial move that sparked criticism. In 1922, he held a meeting with Klan leader Edward Young Clarke, believing that both groups had mutual goals of racial separatism. This decision was widely condemned and led to a decline in his support among Black intellectuals and activists.

5. Opposition from Black Leaders

Prominent Black leaders, including W.E.B. Du Bois and A. Philip Randolph, criticized Garvey’s tactics and vision. They considered his plans, such as the Black Star Line and a pan-African empire, unrealistic and accused him of misleading Black communities. Randolph’s publication, The Messenger, led a “Garvey Must Go” campaign to expose what they viewed as financial mismanagement and false promises. They believed that his plans for black progress, including the Black Star Line and the establishment of a pan-African empire, were unrealistic and ill-advised; they considered the Universal Negro Improvement Association’s grandiose titles and military regalia to be preposterous; and they thought Garvey, with his assumption of a regal posture under the title “Provisional President of Africa,” to be little more than a self-aggrandizing buffoon. A. Philip Randolph, who had introduced Garvey to his first American audience on a Harlem street corner, said Garvey had “succeeded in making the Negro the laughingstock of the world.”

6. Legal Troubles and Imprisonment

In 1923, Garvey was convicted of mail fraud related to the sale of Black Star Line stocks. Despite protests from supporters, he served nearly two years in a U.S. federal penitentiary. The Attorney General at the time, John Sargent, received a petition with 70,000 signatures urging for Garvey’s release. Sargeant warned President Calvin Coolidge that African Americans were regarding Garvey’s imprisonment not as a form of justice against a man who had swindled them but as “an act of oppression of the race in their efforts in the direction of race progress.” Eventually, Coolidge agreed to commute the sentence so that it would expire immediately, on 18 November 1927. He stipulated, however, that Garvey should be deported straight after release. On being released, Garvey was taken by train to New Orleans, where around a thousand supporters saw him onto the SS Saramaca on 3 December. The ship then stopped at Cristóbal in Panama, where supporters again greeted him, but where the authorities refused his request to disembark. He then transferred to the SS Santa Maria, which took him to Kingston, Jamaica. He claimed prejudice from Jewish and Catholic communities played a role in his legal troubles.

7. Political Aspirations in Jamaica

Upon returning to Jamaica, Garvey established the People’s Political Party in 1929 and briefly served as a city councilor in Kingston. He aimed to implement policies such as land reform, a minimum wage, and the development of educational institutions. Garvey attempted to travel across Central America but found his hopes blocked by the region’s various administrations, who regarded him as disruptive. However, financial difficulties forced him to leave Jamaica for London in 1935.

8. Final Years in London

Garvey continued his advocacy in London but struggled to regain his influence. His anti-socialist stance distanced him from other Black activists, and he faced financial hardship. In 1940, after suffering a stroke, he passed away in relative obscurity.

9. Posthumous Recognition

Garvey’s legacy endured long after his death. In 1964, his remains were reburied in Jamaica’s National Heroes Park, and he was officially declared a national hero. His teachings inspired movements such as the Rastafari movement and influenced leaders like Malcolm X and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. King Jr. once said of Garvey: “He was the first man, on a mass scale and level” to give millions of Black people “a sense of dignity and destiny.”

10. Presidential Pardon and Continued Influence

On January 19, 2024, President Biden granted Garvey a posthumous pardon, acknowledging the unjust prosecution he faced. Howard University School of Law professors and students helped to secure a posthumous pardon for civil rights leader Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr, ONH on the eve of the Martin Luther King, Jr. national holiday The first national hero of Jamaica and leader of the U.S. Back to Africa political movement of the 1920’s, Garvey founded the United Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA) to promote unity and pride amongst all Black people across the globe.

For the last 15 years, Howard University professor Justin Hansford has been working with Garvey’s son, Julius Garvey, M.D., who has championed the push for his father, who died in 1940, to receive a posthumous presidential pardon with an acknowledgment that he was unjustly charged. The Congressional Black Caucus, led by Caribbean-American Congresswoman Yvette D. Clarke, also played a significant role in advocating for this clemency. The pardon came years after a campaign begun to push President Obama, the first black US President, to grant the pardon. He did not. In a media release on Sunday, Jamaica Prime Minister Andrew Holness said this is a momentous step toward righting a grave historical wrong committed against one of the most significant civil rights leaders and pan-Africanists in history.

“Today, January 19, 2025, will forever be remembered as a day of triumph for justice and a proud moment for the people of Jamaica. The removal of the unjust stain on Marcus Garvey’s name restores the full dignity and honor he has always deserved as a champion of freedom, empowerment, and equality,” Holness stated, while expressing gratitude to Biden, private citizens who signed petitions, the Jamaican diaspora, friends of Jamaica and successive Governments of Jamaica who lobbied for the pardon.

Garvey’s legacy remains a beacon of Black pride, self-reliance, and unity, inspiring generations worldwide.

Related News

Caribbean-Born Congressman Welcomes Israel-Hamas Ceasefire

Dominican American Influencer Killadamente Dead At 27

Baptist Health International and Cayman Islands Health Services Authority Join Forces for ...