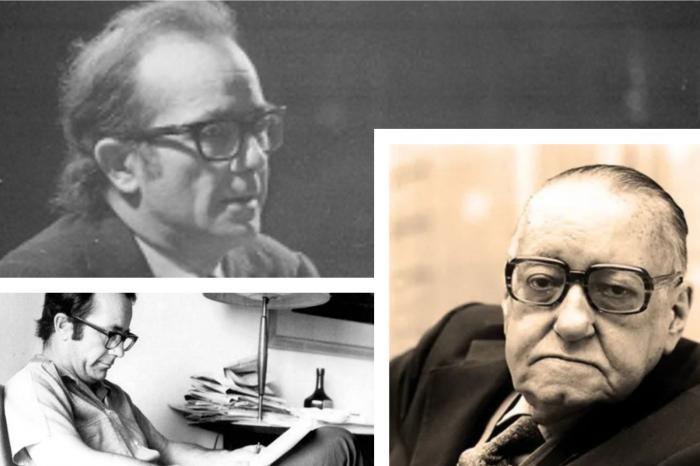

With Alejo Carpentier it usually happens in Cuba what it did with Rodolfo Walsh in Argentina: a certain kind of intellectuals strips them of their ideas and raises them to a quasi-babble threshold in the world of letters... and harmless, it must be said.

Moved, at times, by dilettantia and the lack of a thorough reading of their respective works; at others, by very intelligent and studious characters who, upon recognizing the irreconcilable differences with those they have reviewed, place them at the top, yes, but allow themselves an arrogant pause to save their conscience, to say: they were wrong.

That presumed mistake, “opportunely” pointed out, is almost always, in Carpentier and Walsh, to have stained their literary and journalistic work with social commitment.

Carpentier and Walsh, however, launched strong warnings about this behavior, not at all new, of our intellectuals nostalgic for the purity of the pen.

Social democracy constantly rescues the Argentinean's mastery in writing Operation Massacre, and his stance against Jorge Rafael Videla's dictatorship.

Social democracy does not like dictatorships, but neither do communists, and tries to equate them in the most simplistic senses. Perhaps that is why, in order not to be reminded of what a dictatorship is, it avoids evoking that detailed Open Letter to the Military Junta, written in 1977 by a certain Rodolfo.

A Rodolfo who had thrown himself into the urban guerrilla of the Montoneros, who had developed and directed from the shadows a news agency (anchor) that in no way resembled those of the big liberal press that still today have the information monopoly in many of our Third World lands.

This Rodolfo, who had fully engaged in a counter-hegemonic enterprise that had been named Prensa Latina, and who had already warned, as he recalled its first director, the also Argentine Masetti, about "how names are built and oblivion is woven.

Carpentier, with a longer life, wrote more and not with less “violence” when it came to social justice in our lands.

If in the 1970s there was a Retamar who lashed out against a Borges, in 1961 there was a certain Alejo who pounced against the inconsistencies of a Darío, against the gospel of colonization in Africa raised by a Zola, and who claimed that, for Rodó's Ariel to mean something more than a graceful digression, it would have been necessary for the author to “study a bit of Political Economy”.

This Alejo, who had said: “It is not in vague cabinet theories, in coffee gatherings, in erudite colloquiums, where the solutions to the fundamental, vital problems of this continent - a continent whose unquestionable unity, in certain aspects, is not to be sought in the use of a language common to many countries, but in the existence of identical or similar problems”.

A man of this disposition had founded, with Fidel, the National Printing House of Cuba on a day like today, but in 1959. The first thing he did then was to reproduce 100,000 copies of Don Quixote.